How sharply does the line fall between Eastern and Western thinking? Many contrasts can be taken to advance the view that the West and East think in strikingly different ways. Richard Nisbett’s Geography of Thought is the seminal text for discussing these differences: he illustrates that where Western thought is individualistic, Eastern is collective and where Westerners break down problems analytically, Easterners often think holistically (Nisbett, 2003). This is a generalisation, but on average, and by average I mean through statistically meaningful samples, this contrast holds and notably, it goes deeper than surface level psychology.

In Robert Sapolsky’s Behave (Sapolsky, 2017) and Determined (Sapolsky, 2023), he illustrates that when Westerners are presented with a certain spherical object and asked about it, they often look at its individual qualities: how does it feel, what does it look like? By contrast, Easterners were often found to ask, how does this object relate to the world around me? Of what context would it be in? Importantly, Sapolsky suggests that these differences are linked to unique neurobiological factors. fMRI studies show different neural activations in attentional control networks when asked to focus on context vs objects (Hedden et al., 2008). Western participants show more activation in the frontoparietal attention network (FPN), an area crucial for goal directed cognition and flexible attentional control (Vincent et al., 2008), when forced to attend to context. In other words, because Westerners prefer object focused processing, when they are forced to focus on context, they need to recruit the FPN more heavily, engaging top-down control to override their default bias. Eastern participants, on the other hand, showed the opposite pattern for object-focused attention, finding it harder to attend to object focused processing but easier to focus on context.

This opens up a world of interesting thoughts. Often we are instructed and told, in difficult situations, that context matters. History can act as good example here. People often find themselves asking, when discussing a historical topic or figure, “but why would they do that?”. Being more specific, take the appeasement of WWII Chamberlain undertook. Common reactions are: "how could Chamberlain have been so naïve?". Other than falling for the hindsight bias of knowing the outcome of Hitler’s decision to invade Poland, the lack of contextual understanding could be a genuine cause to ask this initial question. Britain was exhausted from WWI, had limited military readiness, and public opinion was strongly against another war (USHMM, 2024). Without context, the decision looks like weakness, madness even; with context, it’s a calculated, if inherently flawed, political move. Therefore, the reactions to Chamberlains decision are not necessarily through a lack of appropriate critical thinking but due to a lack of contextual understanding, and this deficiency is perhaps because on a neurobiological level, as a Western society we struggle more on average to grasp and situate experiences within a wider context.

Notable differences between Eastern and Western attitudes are also reflected in other neural structures. The amygdala - often oversimplified as a “fear centre” but more accurately a salience detector involved in threat appraisal and emotional processing - responds differently depending on cultural context. A study found that both East Asian and Western participants showed greater amygdala activation when viewing fearful faces from their own cultural group, compared to other groups (Chiao et al., 2008). This suggests that emotional salience is culturally mediated: what registers as “threat” or emotionally relevant is filtered through shared identity and learned cultural cues. Cultural frameworks don’t simply shape how people think, but also what kinds of social signals their brains prioritise at the level of perception itself.

How far these differences extend back and for what reasons are not questions that can easily be answered, though the differences appear strongly in Ancient Eastern and Western philosophic traditions. Plato’s Forms offer one of the clearest expressions of the Western analytic tendency (Plato, 2007). Here, truth lies in abstraction, not flux; a thing has an essence, an eidos, which excludes contradiction. Plato felt that the objects of this world are, in some sense, “unreal", precisely because they can both be X and not X. A work of art, for example, may seem beautiful to one person and ugly to another. Or take the more familiar example of a spherical object: no matter how round it appears, it can never be perfectly so, and so must also be called not round. To Plato this meant objects of the physical world that we exist in are not truly real.

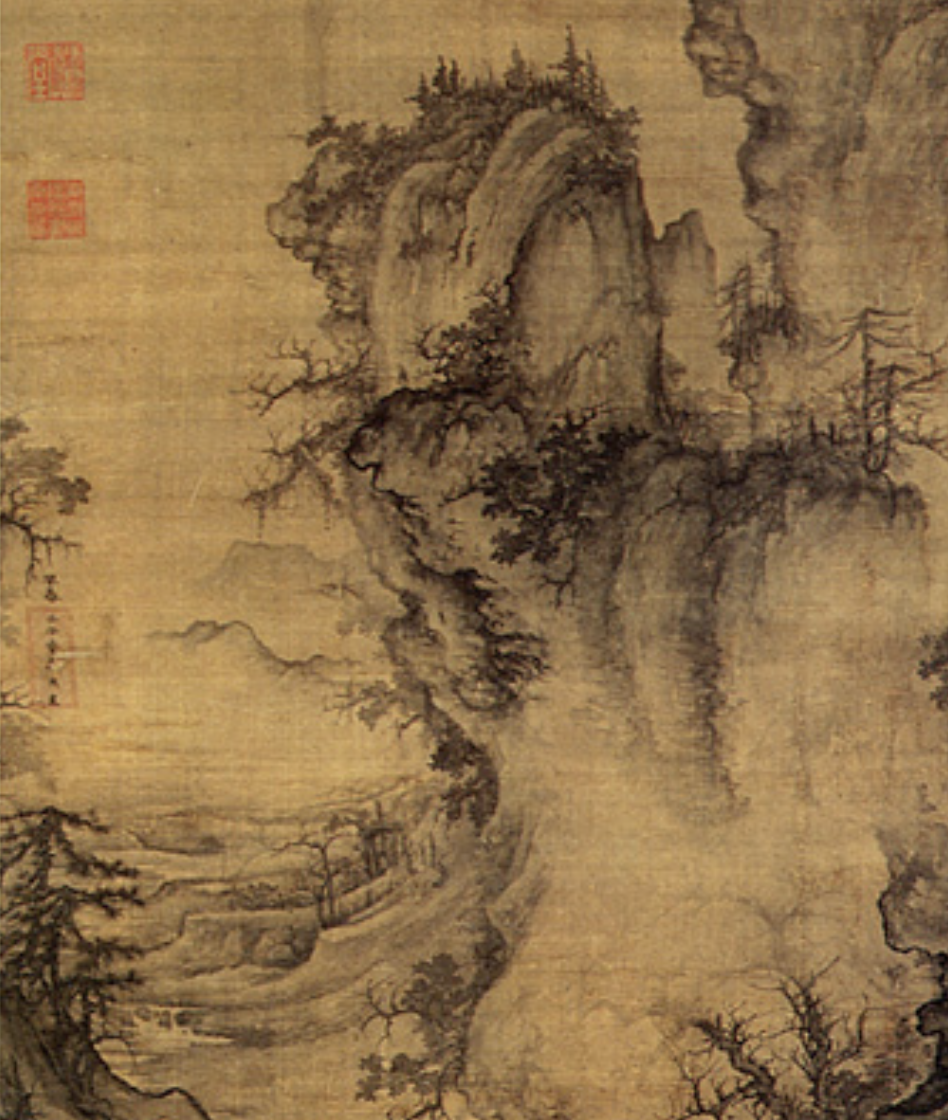

To resolve this, Plato introduces the Forms. The Forms are real because they are pure - a Form can possess complete roundness and only that quality, which we then somehow draw on to grasp the notion of roundness. Within the realm of Forms, it would be nonsensical to suggest that the pure round object also possesses non-roundness. This is a kind of plurality, or if you like, an individuality - a characteristic way of thinking about knowledge, about epistemology. The Ancient text the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu (though the historicity of Lao Tzu himself is debated) takes the opposite approach (Lao Tzu, 2008). The Tao does not deal in plurality, but suggests everything that exists does so holistically. Taoist thought is grounded in paradox - in "the both", does the Tao suggest something to exist. The Tao contains its opposite; roundness and not-roundness coexist in flux. An object is not less real because it embodies seemingly opposing traits at the same time; rather, it is precisely because it does so that it becomes part and essence of the Tao. A mountain has both a peak and a valley, and both must exist for the mountain to exist.

Though purely speculative, if we accept that neurobiological development is shaped by the interplay of genetic inheritance and environmental pressures, then the philosophical separation that has persisted between East and West may, in some way, have influenced the contrasts we observe when we place ourselves in fMRI scanners and uncover our neuronal differences. The Plurality and focus on distinct individual characteristics found in Platonic dialogue has disseminated into the conscious thought of Westerners and equally, that of the Tao and its collectivist, holistic approach finds itself embodied in the views of Easterners.

This difference extends further into other philosophical texts of East and West. Plato laid the foundations of an analytic tradition in philosophy, one that would later develop through Spinoza’s axiomatic method of rational thought, to Hume’s dismantling of pure rationality, on to Kant and then the rise of a new analytic tradition in that of Frege and later the Vienna Circle, Bertrand Russell and Wittgenstein (Russell, 2004). Regardless of the specific arguments, the broad body of this Western philosophical tradition is and continues to be analytic rather than holistic (and this is acknowledging the broad divide within Western Philosophy between Continental and Analytic).

In contrast, other Eastern philosophical texts such as The Art of War approach complexity not through analytic dissection, but through elegant distillation (Sun Tzu, 2002). Where the Western tradition often seeks to build vast systems of thought, The Art of War conveys strategic and philosophical insight through remarkable simplicity, grounding its claims in the essence of lived, practical realities. It neither over-analyses nor endlessly dissects its own claims. Though The Art of War predates Western philosophical schools by centuries, making a direct comparison difficult, its influence remains strikingly alive. It continues to be widely read and studied extensively in China today, not only as a historical document but as a strategic and cultural touchstone (NDU Press, 2014), (Asian Studies Association, 2016).

Its endurance allows for a meaningful comparison with the lasting impact of Western philosophical texts - Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Hume - whose ideas continue to shape Western intellectual and cultural frameworks. In both cases, there exist undertones of ancient thought in the structure of modern patterns of reasoning. With that in mind, again we see the pattern where the Western tradition tends to dissect, qualify, and abstract, and the Eastern thought of Sun Tzu speaks in statements that are self-contained and paradoxical. The text presents wisdom as something to be absorbed, not endlessly unpacked. Wisdom is expressed in tautological, self-evident phrases, which reveal their depth through practice rather than through discursive argumentation. It demands fluid adaptation, not linear explanation.

Clausewitz famous book On War is an apt comparison to make, as his book operates in the opposite way (Clausewitz, 1982). Clausewitz thinking rests on linear causality, accumulation of variables, and an abstract theoretical framework layered over the reality of war. To Western readers, The Art of War often seems abstract precisely because it does not provide these analytic supports. Its statements appear too simple, almost incomplete, and ironically must be forced through the same interpretive machinery applied to western philosophical texts. We interrogate its paradoxes rather than accepting them on their own terms. Clausewitz’s On War makes this difference explicit. In his chapter The Art or Science of War, he begins:

“The choice between these terms seems to be still unsettled, and no one seems to know rightly on what grounds it should be decided, and yet the thing is simple. We have already said elsewhere that ‘knowing’ is something different from ‘doing.’”

No such treatment of semantics appears in The Art of War. There, understanding is intuitive and practical. Clausewitz approaches war as a theory to be built. Sun Tzu approaches war as something to be read and felt intuitively.

Finally, we have mythology. I was born in the Year of the Snake. Though I attribute no significance to this, the contrast between Eastern and Western conceptions of the snake are once again illustrative of a different pattern of thought between the two spheres. The snake in Western thought is often used to denote untrustworthiness, slipperiness, and latent danger, qualities reflected in the common phobia of snakes (ophidiophobia)*. Studies show that the fear of snakes is particularly prominent in the West: one psychometric study estimated that around 2–3% of people meet criteria for a snake phobia (Polák et al., 2016), accounting for roughly half of all animal phobias and another study found general anxiety about snakes in over half of a UK sample (53.3%) (Davey, 1994).

In Chinese thought, the snake has a different symbolic life. According to legend, the Jade Emperor invited animals to a great race to determine the order of the zodiac. The snake, hidden in the horse’s hoof during the river crossing, startled it at the last moment and crossed just before, becoming the sixth animal in the cycle. The tale symbolises the subtlety and strategic intelligence of the snake, emphasising these qualities over that of deceit. Traditional associations cast the snake as Yin, linked with the trine group of Snake, Rooster, and Ox - embodying wisdom, discipline, and perception and because Snakes shed their skin, they are also symbols of renewal and transformation.

Unlike in the West, where the snake evokes deceit and danger, Chinese culture represents snakes as possessing wisdom, elegance, and adaptability, closer to the Jungian archetype of the Sage, rather than a tempter or deceiver. One might wonder whether, if similar neuroimaging studies were conducted among participants immersed in such cultural narratives, the neural and emotional responses to the snake would differ. Within Taoist philosophy, what the snake embodies is not singular, it is both fear and its opposite. In Plato’s logic, a snake could only repel or attract, but never both. For the Tao, these opposites are inseparable, coexisting within the same universal whole. This narrative of wholeness, of seeing the world as a domain full of contextual layering as opposed to distinct qualities found in a meta or other world, is perhaps the key dividing line, encompassed in our actions and in our neurobiology. What this distinct contrast might actually mean and has meant is another question entirely, whose answer(s) are full of possibility.

*Interestingly, these studies on snake fear found that disgust was a key driver of fear, a finding that aligns with neuroscience showing that the insula, a brain region associated with disgust and interoceptive awareness, activates strongly in such responses (Calder et al., 2000), (Wicker et al., 2003). The visceral revulsion we feel often creates fear, conditioning us to avoid what we find repulsive. Cultural exposure shapes these boundaries: what one culture recoils from, another accepts as normal. Many Westerners find the idea of eating insects revolting, yet insects are a delicacy in much of Asia. A small literary echo of this comes from Lonesome Dove, one of the great novels of the American Wild West, where the new cook, 'Po Campo', introduces the group of cowboys to eating grasshoppers (McMurtry, 2015). Initially disgusted, they eventually try the grasshoppers and find them delicious. “A big grin” spreads over the face of one of the cowboys named 'Deets', as he realises how tasty they are. What follows is a familiar dynamic in social psychology: as a few individuals try something new, others observe, infer its acceptability, and follow suit. Within moments, the entire group is eating grasshoppers. This is a classic case of social proof - or, more technically, normative social influence - where behaviour rapidly shifts once it becomes socially validated by the group.

- Asian Studies Association. (2016). New Perspectives on the Sunzi (Sun Tzu).

- Calder, A. J., Lawrence, A. D., & Young, A. W. (2000). Neuropsychology of fear and loathing: The role of the insula in disgust. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 1(1), 54–61.

- Chiao, J. Y., et al. (2008). Cultural specificity in amygdala response to fear faces. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(12), 2167–2174.

- Clausewitz, C. von. (1982). On war (M. Howard & P. Paret, Eds. & Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1832)

- Davey, G. C. L. (1994). Self-reported fears to common indigenous animals in an adult UK population: The role of disgust sensitivity. British Journal of Psychology, 85(4), 541–563.

- Fredrikson, M., et al. (1996). Prevalence of specific fears. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(8), 675–685.

- Hedden, T., Ketay, S., Aron, A., Markus, H. R., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2008). Cultural influences on neural substrates of attentional control. Psychological Science, 19(1), 12–17.

- Lao Tzu. (2008). Tao Te Ching (D. C. Lau, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published ca. 4th century B.C.E.)

- National Defense University Press. (2014). Sun Tzu in Contemporary Chinese Strategy.

- Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently... and why. New York: Free Press.

- McMurtry, L. (2015). Lonesome Dove. Picador Classic. (Original work published 1985)

- Plato. (2007). The Republic (D. Lee, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published ca. 380 B.C.E.)

- Polák, J., Sedláčková, K., Nácar, D., Landová, E., & Frynta, D. (2016). Fear the serpent: A psychometric study of snake phobia. Psychiatry Research, 242, 163–168.

- Russell, B. (2004). A history of Western philosophy. Routledge Classics. (Original work published 1945)

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. New York: Penguin Press.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2023). Determined: A science of life without free will. New York: Penguin Press.

- Sun Tzu. (2002). The Art of War (J. Minford, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published ca. 5th century B.C.E.)

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (2024). The British Policy of Appeasement toward Hitler and Nazi Germany

- Vincent, J. L., Kahn, I., Snyder, A. Z., Raichle, M. E., & Buckner, R. L. (2008). Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Journal of Neurophysiology, 100(6), 3328–3342.

- Wicker, B., Keysers, C., Plailly, J., Royet, J. P., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (2003). Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron, 40(3), 655–664.