Originally titled Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying, this is one of Turner's most volatile works. Turner's themes are vast and often pit man against some great natural event. His work fits well with the ideas in the Shadow Line essay, where enduring what nature and life throws at us creates something hardier and sturdier. Nature's trials call forth an inner strenght within ourselves; that shadow line that we all may cross at some point in life emboldens to state in our manner and bearing that we have experienced something.

The death of Socrates was a pivotal moment in Western philosophical history. Plato, having witnessed the death of his beloved mentor, became disillusioned with the idea that a democratic political structure could permit the execution of such a noble and just man. This moment, in many ways, led to the conception of Plato’s ideal state in The Republic. Grief is explicitly shown in the painting, with Plato sitting aged and withdrawn at the foot of the bed. The work is one of the most notable achievements of Neoclassical art and acts as a visual manifesto for reason and intellectual integrity.

Painted just before the French Revolution, the painting carries strong political motifs, depicting a martyr standing against the tyranny of the state and using philosophy as a beacon of light and reason to guide the way into a new age. Socrates appears every bit the great philosopher: stoic in the face of death and, ironically, just as in the Phaedo (Plato’s account of his death), consoling his followers rather than being consoled by them.

The Orientalist movement, put simply, was the West’s attempt to romanticise the East. Artists projected their own perspectives and fantasies onto Eastern subjects, producing depictions of Eastern culture through a distinctly Westernised lens. What emerges is not the East as it was, but the East as it was imagined.

Given that the myth of the snake is discussed in Plurality and Singularity, and that The Snake Charmer is one of the most reproduced works of Orientalism, its inclusion in this essay felt fitting. The painting embodies both cultural symbolism and cultural distortion, making it a sort of visual echo of the philosophical divide explored in the essay.

In later writings, Freud would eventually see outwards beyond the inner psyche of man and realise, as the psychologist Alfred Adler earlier realised, that the child’s anguish is not as much against himself as against the insurmountability of nature; the external and unconquerable, unquestionably powerful realm that we live in. The Shadow Line, of which this work is featured, is an essay that explores the coming of age through hardship, and this hardship is often characterised through a personal battle with nature. A Storm in the Rocky Mountains is a testament to the sublime in nature: this large, wonderful yet often fatal power found on earth.

Picasso’s Guernica was painted after the Germans bombed the town during the Spanish Civil War. It is a symbolic portrayal of suffering conveyed on a mass scale, its size and detail magnifying the atrocity of the act. Guernica stands as a testament to the power of moral outrage in art, yet Picasso himself was no pure moralist, known for his cruelty in relationships and his jealous, narcissistic persona. The work serves as a motif for the broader themes explored in the essay, Separating the Art from the Artist.

Redmond was a deaf Californian painter and a close friend of Charlie Chaplin who brought Californian landscapes to life through his Impressionist style. The bright yellows, distant mountains, and lush green foliage are evocative of a place of hope, dreams, and agricultural potential, themes that Steinbeck explored extensively in The Grapes of Wrath, In Dubious Battle, and East of Eden. Redmond’s painting depicts the background setting of Steinbeck’s Salinas Plains, a moral stage upon which his characters struggle to create and live out their fated lives. This makes Redmond’s work, particularly Spring in Southern California, especially appropriate for the essay Just East of Eden there is Free Will.

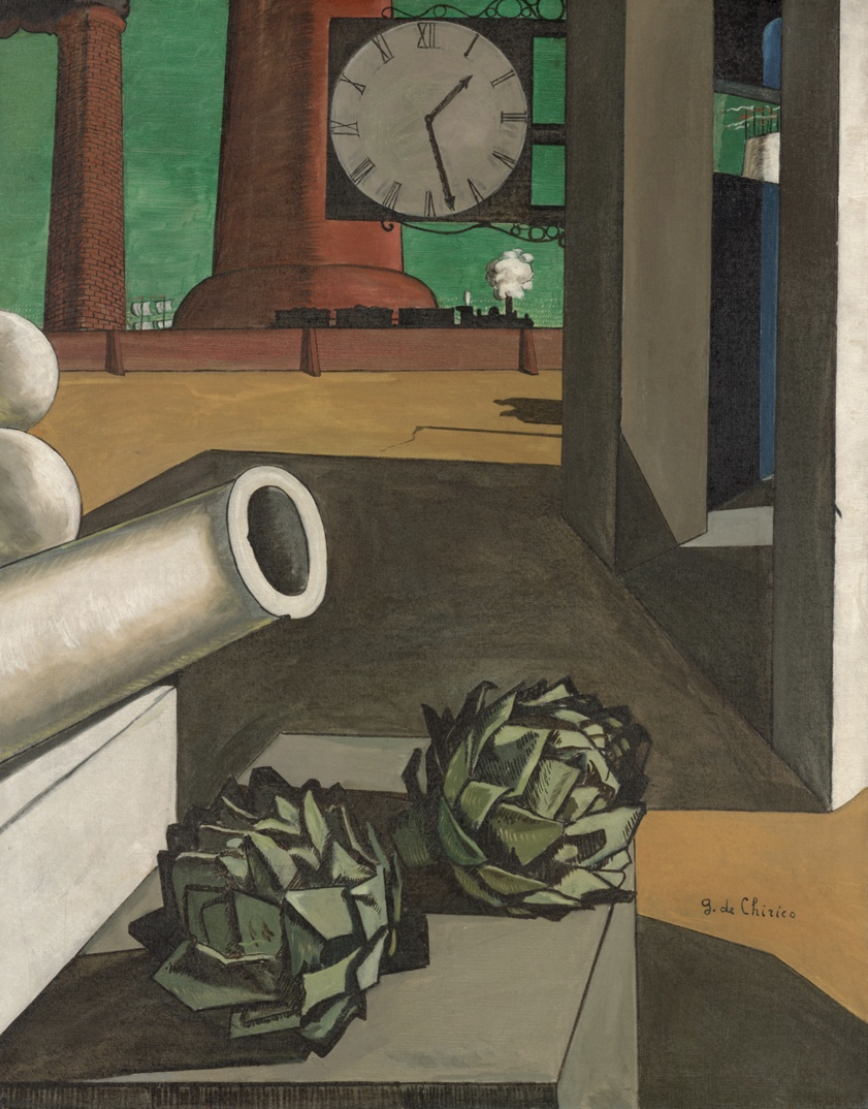

De Chirico painted The Philosopher’s Conquest in 1914, as science entered a new phase, proceeding from the Industrial Revolution but with darker and more potent consequences. The Industrial Revolution had already claimed the natural beauty of many landscapes, and now science was beginning to weaponise humanity in far more lethal ways, with poison gas and machine guns introduced to the trenches of the First World War with horrific results. The Greek derivation of philosophy means “love of wisdom,” and the study of philosophy included within it the study of the natural sciences. Modern science has emerged from this philosophical tradition, and de Chirico seems to point to the incessant drive of scientific thought to permeate all parts of life and ‘conquer’ all it’s elements, from time symbolised through the clock and train, and physical through the spaces and distant structures of the artwork.

Yet the elements of the painting are placed sporadically and at great distance from one another, appearing incongruent and separated by large expanses of empty space. There is a sense that although science possesses great explanatory power over the physical world, it also has its limits. It cannot perfectly map or connect all elements of existence, and so while science progresses, the world can still feel existentially and metaphysically strange to us as individuals. Science alone cannot fill this void.

The story of Eden portrays what could be considered the first biblical illustration of free will, a decision that led to Christian moral catastrophe and the subsequent fall of man. Rubens and Brueghel’s depiction overflows with abundance, life, and beauty, a paradise so rich and sensuous that the temptation feels almost inevitable. The harmony depicted in the scene heighten the tragedy of the choice that follows. Existential freedom carries with it the possibility of a great and sudden downfall.

In this way, the painting therefore does not merely represent Eden, but the fragile moment before knowledge of the outside, ‘free’ world, fractures the delicate innocence of the inhabitants of Eden. It is therefore fitting that the work appears in the essay Just East of Eden there is Free Will, where freewill is explored and ultimately questioned - our freedom is a stubborn and persistent illusion that nevertheless must be upheld to live morally.

Vermeer’s The Astronomer was painted during the Scientific Revolution and seems to illustrate a perception at the time (and still today), that a truly curious and fascinated mind is the greatest requirement for achieving breakthroughs in understanding the natural world. The man depicted (possibly Antonie van Leeuwenhoek) is filled with a burning desire to understand, reaching out to grasp the globe, bathed in light as though its secrets might be revealed to him.

The philosophy of science provides a lens through which we can understand how to do better science, and this artwork was included specifically in the essay Philosophy of Science to represent the belief that the scientist must also possess a certain philosophical disposition: the ability to self-critique and to welcome error as a natural path in the pursuit of truth.

Nietzsche prescribed himself long, vigorous walks in the Swiss Alps, where he developed many of his lines of thought, and famously wrote in Twilight of the Idols, “All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.” When reading Nietzsche, one senses a manic energy, an irrepressible spirit that demands to be spoken into being. This context makes Munch’s portrait of Nietzsche all the more striking, as it depicts the German philosopher in a state he was rarely in: static and at rest. Though his body appears still, his mind seems distant, absorbed in the formulation of a philosophy whose influence remains widespread.

In the propagation of Nietzsche’s ideas, history has shown how fragile radical thought can be when placed in misguided hands. While his work has inspired greatness in the individual, it has also been repeatedly and tragically misattributed to the political horrors of Nazism.

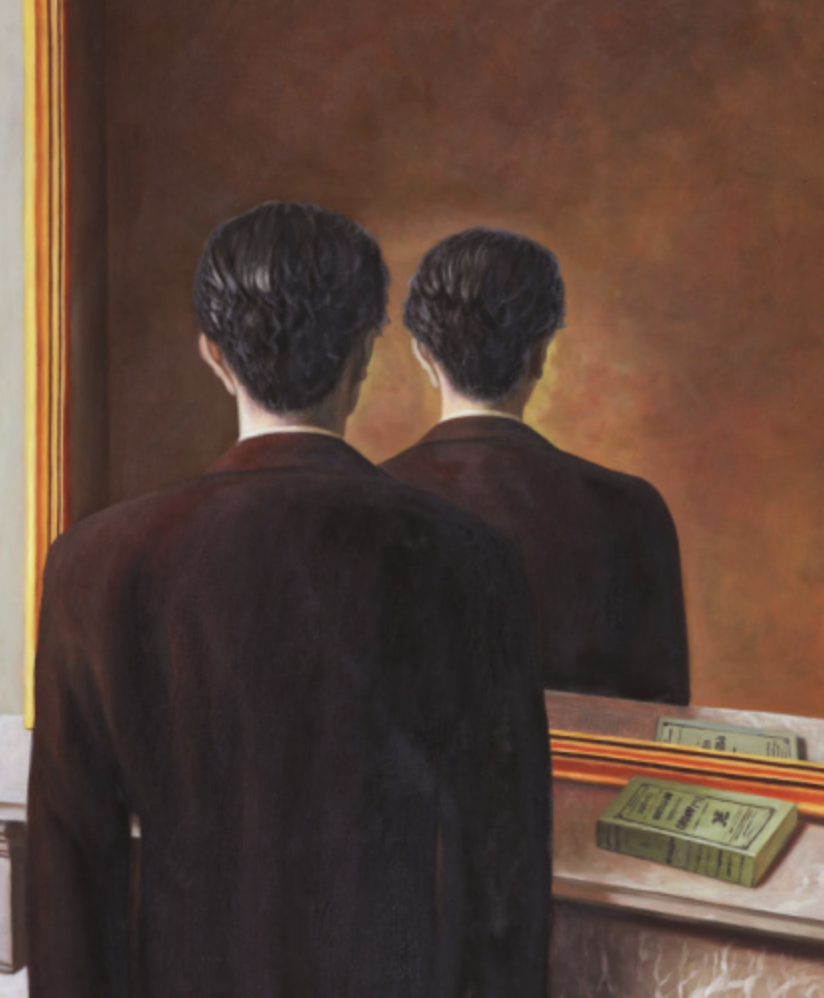

At its core, La Reproduction Interdite is about the failure of self-knowledge. We all believe we know ourselves, yet why was so much emphasis placed by the Greek philosophers on “knowing thyself”? Or, as Plato writes in the Apology (recounting the final days of Socrates), “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Magritte emphasises what ancient wisdom was so keen to reveal: that in reality we know very little of ourselves, and that the habitual, customary glance in the mirror we engage in regularly does nothing to show who we truly are.

We are reminded of a Jungian shadow, buried deep within us, that cannot be revealed by superficial, aesthetic examinations of ourselves. Can we truly say, as we walk out into the external, public world, that what we produce through social engagement is a faithful reflection of who we really are? We all engage in some form of cognitive dissonance and Magritte captures this brilliantly.

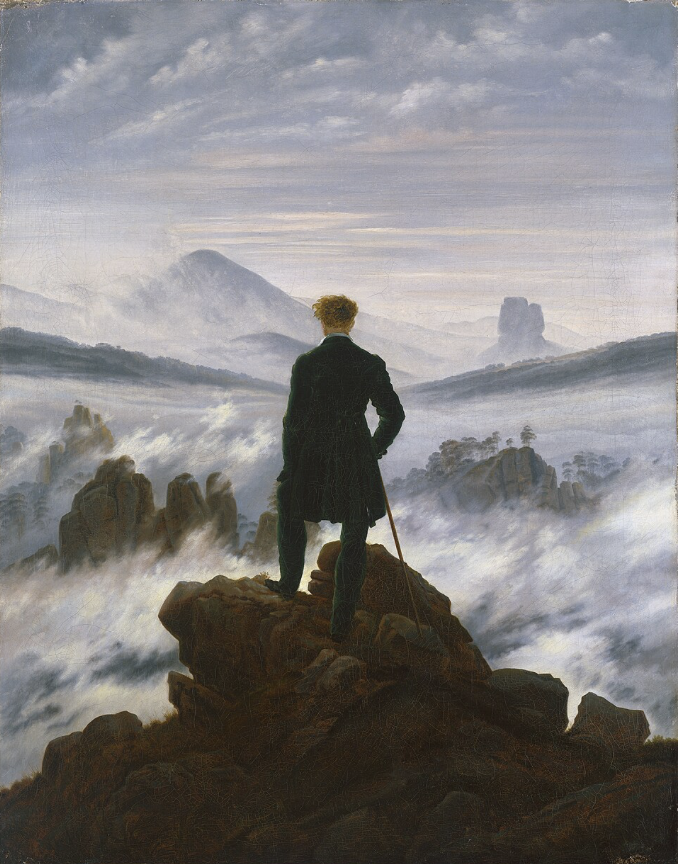

Solitude might be one of the most valuable traits for a philosopher. Others’ views and opinions are important in refining one’s outlook and correcting errors; however, much of the time we begin to confuse clarity with conformity, and the rhythms of societal life can quickly become chains that weigh us down. As put by Seneca in his Letters, “I never come back from the crowd without having lost something of myself,” or, more drastically, by Sartre: “Hell is other people.”

It is necessary for the philosopher to step away from established thought in order to critically analyse the thoughts of others, the thoughts of their society, and their own thoughts. Solitude is the panacea, the key to this reflection. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is the epitome of the contemplative thinker, considering the world from the heights and isolation found in nature. In a sense, it is the Platonic ideal of what a philosopher-king should be: elevated above society, physically and intellectually, with the fog below representing the obscuring and muddled thought of others.

Yet the man is also dwarfed by the surrounding nature: the sea of fog, the looming mountains, and the vastness of the sky echo themes within Romanticism. We might feel important, but we should acknowledge there are things far larger than ourselves. As Blake writes in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, “The roaring of lions, the howling of wolves, the raging of the stormy sea, and the destructive sword, are portions of eternity too great for the eye of man.”

In Rembrandt’s Philosopher in Meditation, light streams into a room of darkness, focusing solely on the seated philosopher. The viewer begins to realise that the light is not generated externally, but internally, from the thinker himself, who brings clarity of thought into a shadowy and confusing world. The shadows represent our ignorance, the light our reason, and perhaps no famous quote serves this analogy better than that of Socrates: “There is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance.” The good philosopher sheds light on life with clarity and purpose, not to obfuscate, but to reveal what is already there.

The philosopher is shown sitting in his home rather than in a study or place of academia, suggesting that good philosophy is not an esoteric practice but a lived one. As Aristotle writes in his Nicomachean Ethics, “Moral excellence comes about as a result of habit. We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, and brave by doing brave acts.”

Plato and Aristotle are the central pillars of Western philosophy. Often, Plato’s Republic is described as the single most influential book in Western philosophy, perhaps after the Bible, and certainly within political philosophy, though very little of Plato’s ideal state exists in our current political climate. Raphael’s The School of Athens, housed in the Stanza della Segnatura, Pope Julius II’s private apartment in the Vatican, brings Plato and Aristotle to life on a grand and majestic scale. Raphael seems as if he was depicting Olympus itself, which makes some sense given that the painting does not represent a specific temple or forum in Athens, but rather an idealised setting in which knowledge is treated as the highest good.

We view the ancients as belonging to a distant era, forgetting that cosmologically, two thousand years is an infinitesimal amount of time. These figures are as real as they ever were, especially given that statistically more people discuss, study, and are unconsciously influenced by these philosophers today than at any other point in history.

We are not privy to the minds of others, unless in the future, where neuroscience takes further leaps into the wrong directions, a dystopian society exists where we can accurately infer whats on anothers mind. As it stands, we currently possess only our own impressions of others.

Monet, I think, captured this essential idea; that what we see is at best an imperfect form of reality, much like the shadows in Plato's cave - where reality is subjected to our own ideas, our own impressions. This same imperfect view of our natural world extends to how we see others, which is why it is included in the essay "You will be judged: the Neuroscience".

Fight with Cudgels evokes the primitive in man, an innate violence between two personalities, clubbing their existence into being through actions encoded deep in their biology. The depiction is akin to that of the biblical clash between Cain and Abel, modernised and focused on many times in literature, perhaps most notably by Steinbeck in East of Eden, whose book is the centre piece of the essay, Just East of Eden there is Freewill.

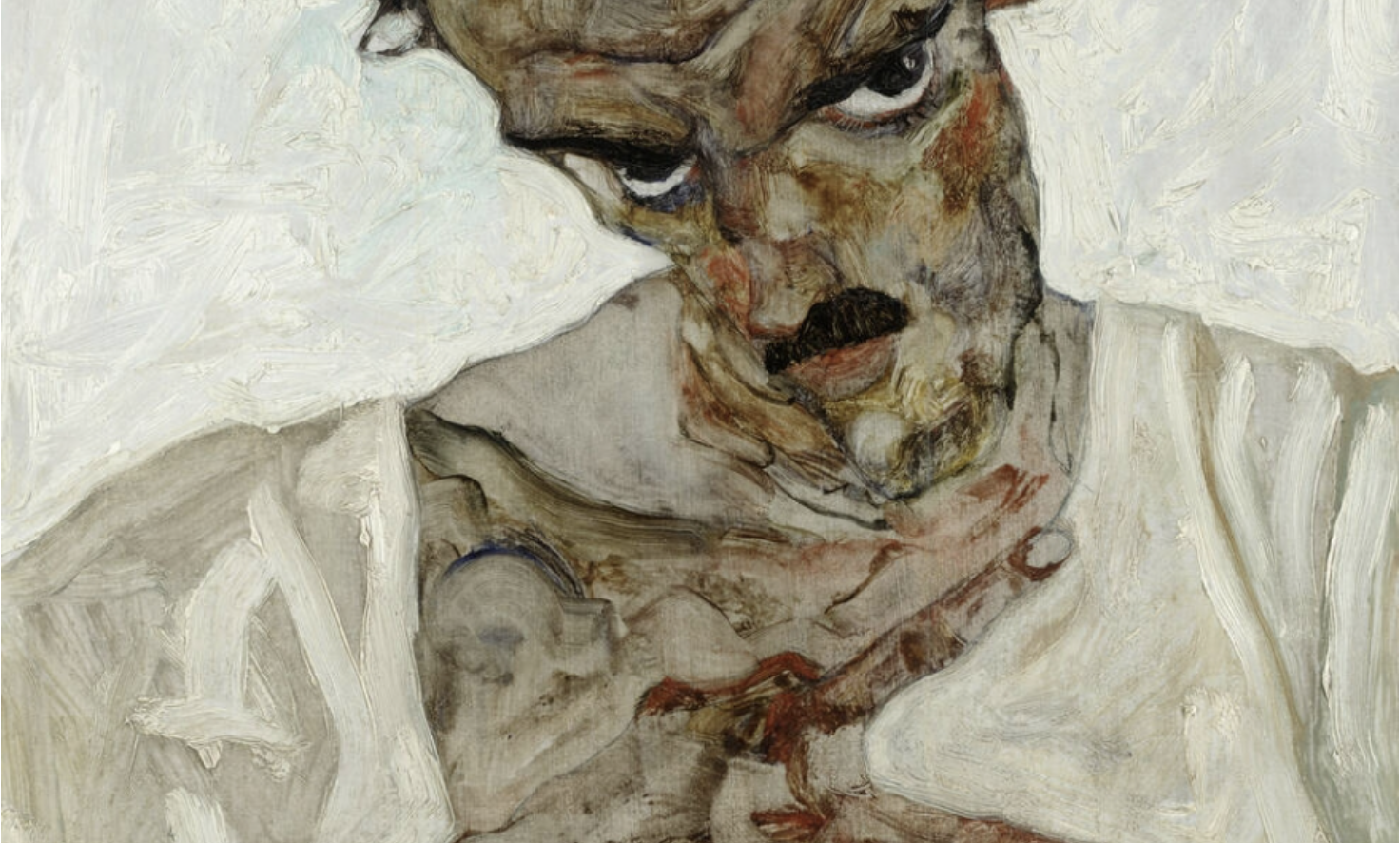

Schiele’s self-portrait is an apt and fitting work through which to reflect on Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo. The painting is at once grandiose, strange, and distorted, and a similar feeling is evoked when reading Nietzsche’s autobiography. One grimaces and yet marvels at the egoism of a man daring the abyss of human madness, teetering just a little too close to its edge.

Nietzsche’s writing on madness in Beyond Good and Evil is both ironic and tragic in its truth: “Madness is something rare in individuals, but in groups, parties, peoples, and ages, it is the rule.” It is a rarity that would eventually strike Nietzsche himself. Schiele’s portrait appears on the cover of Ecce Homo, and it has now humbly made its way into the essay The Paradox of Wisdom.

The evolution of art in both periods of history is constrained by its past, just as we are constrained by our human pasts. New iterations, as art moves forward, represent small breaks from tradition that nevertheless remain influenced by it, precisely because of the need to break away. Like a troubled son who tries to escape the path and actions of his father, he often ends up still embodying some of the traits he once swore never to possess.

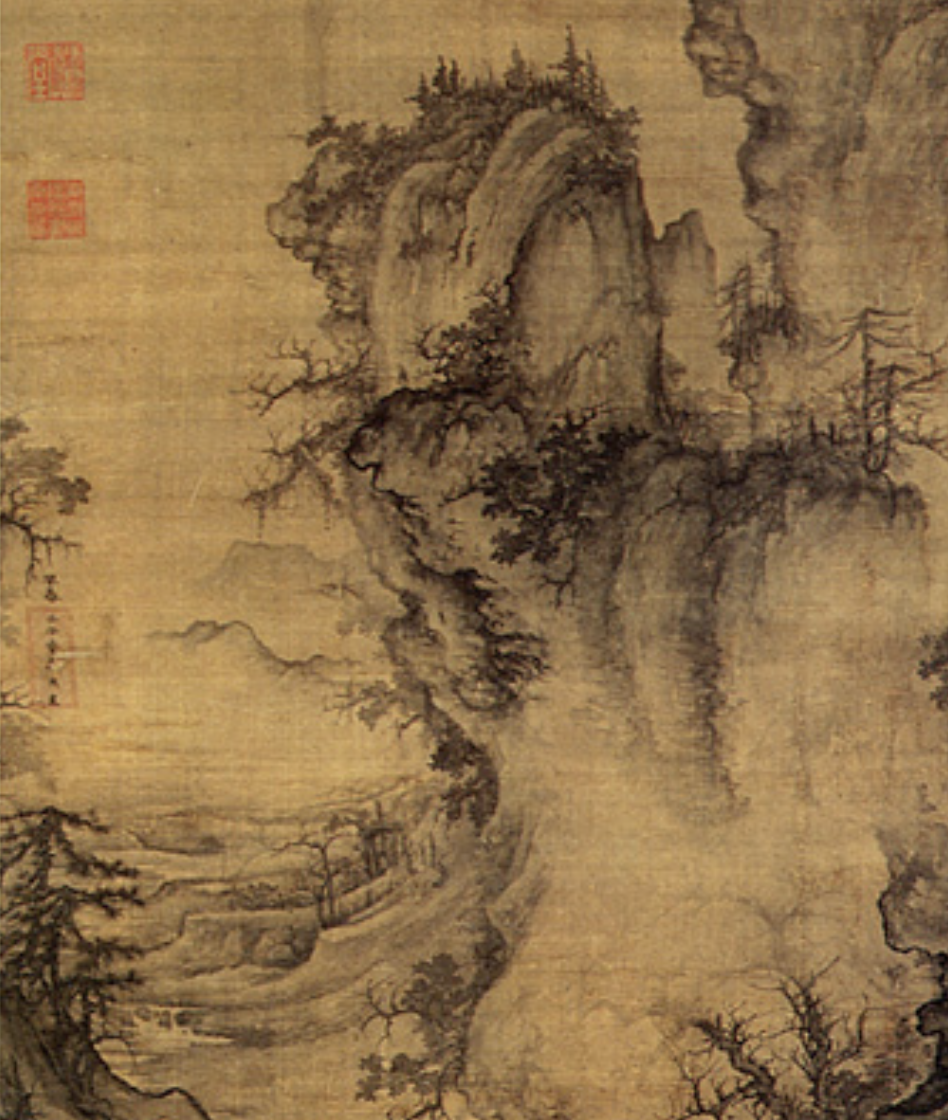

Early Spring, created by Chinese artist Guo Xi during the Song Dynasty and part of the large Northern Song tapestries of the time, is very different from the work of say Japanese artist Hiroshige in the 1800s, yet it remains far more similar to it than to anything Western. Likewise, art of the 1200s, particularly the Western Gothic style, though vastly different from the Romantic art of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, still possesses qualities that are recognisably alike. Early Spring, contrasted to the art of Turner in the essay East & West, poignantly illustrates how our historical and geographical heritage creates what and who we are.

Zao Wou-Ki's Hommage to Monet is an apt representation of blends between Eastern and Western artwork. The piece contains elements of light characteristic of an impressionist painting, however, the brushwork is of a more traditional Eastern technique, with the resulting work being a unique bridge between Eastern and Western styles. This blending, by extension, merges that of Eastern and Western thought, making it an ideal piece to use in the East & West essay on being & thought.

The eye, which encapsulates the sky, asks us if we are seeing the world or if the world is constructed by our seeing it. Though we think vision to be an objective truth, the eye reveals it to be subjective and reliant on the person perceiving the image. Magritte, in his art, challenged the reliability of images, reminding us that the image of a thing is not the thing itself. In much the same way, when we commit judgement on a person, we are not seeing or capturing the person, but something of the person, not what they actually are - leading in many cases to a profound misjudgement of character. The False Mirror felt like the perfect piece to be included in the essay, You will be Judged: the Neuroscience.

Our interactions with others are filled with a plethora of subtle social cues; understandings and misunderstandings are continually made, remade, amended and lead irrevocably down to a certain relation-ship with a person. There is a fantastical neural-chemical dance going on in our brains during social events, especially of the kind where romances are made and broken and status is tested and probed. However, the beauty and the nuance of such occasions is far better captured in Renoir's Luncheon than any brain scan could possibly hope to achieve. The art piece is featured in You will be Judged: the Neuroscience.

Architecture is a powerful way to understand a culture, be it one of past or present. The way a building stands and is built, is in some ways an expression of the ideas of an entire society. Within this architectural expression we can then see the differences between societies, where marble is used in Greek temples, wood is used for Chinese shrines. Though geography was the constraint in the material being chosen, what dictated the differences in design?

It would be imprudent to say that this difference means anything in particular, but we can say that it does show a certain divergence in attitude and thinking. The structures both convey the egos of their creators, their king of kings attitude, but in different ways, to different deities, in different worlds. Hence Turner's Temple of Poseidon was included in the essay Plurality and Singularity: Differencces in Eastern and Western thinking, capturing not only what ancient Greek architecture was, but also it's Western interpretation made by Turner.